David Bowie terrified me. I was a late developer, a shy teenager who looked up to the cool girls at school flashing their well-worn copies of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, reinforcing the feeling that they had joined a club I could never be part of.

He was theirs, not mine. He didn’t belong to me. I was standing outside the door, looking in and not even understanding what I was seeing.

But that didn’t mean he had any less of an impact on my life. He was omnipresent.

I didn’t really get Bowie until Aladdin Sane. The album came out two weeks after my dad survived a catastrophic stroke in April 1973. He was 46. I was 16.

After that, I felt completely lost.

I’d like to say Bowie came to the rescue, but he didn’t. A handsome boy called Mark did. My sister had a 21st birthday party, and he was the DJ. Mark was my first proper teenage crush (I said I was a late developer).

I remember hanging around his decks like a puppy, requesting The Jean Genie – the first single from Aladdin Sane. It had stirred something within me that I found exciting but disturbing. I think we can all guess what that might have been.

Anyway, Mark played my request, which made me fancy him even more. But then he did something totally unexpected. He told me he had a spare copy of the album, which I could have if I wanted it.

Oh. My. God. He’s giving me Aladdin Sane! It must mean he likes me! Am I too young for him?

OF COURSE I wanted it. (The album, I mean… and Mark…)

I cannot begin to describe how much I treasured that album. To begin with, it was simply because He Gave It To Me. But when Mark failed to follow up on what I considered to be the ultimate romantic gesture, I started to listen to it obsessively, poring over the lyrics again and again and feeling baffled and uncomfortable and thrilled in equal measure.

I couldn’t possibly tell my mum I was listening to a record that had lyrics like “Time – he flexes like a whore, falls wanking to the floor”. I wasn’t supposed to know what wanking was. And I certainly didn’t Do It.

I could never talk to my dad about sex before and I certainly couldn’t do it now he’d had a stroke.

That’s why David Bowie seduced me but terrified me. He was about sexual ambiguity, experimentation, scary-crazy stuff that I couldn’t even ask questions about. In my sad, confused state it was just too overwhelming.

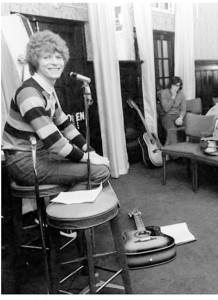

In my late teens I started a band with some friends, as you did in late-Seventies suburbia. We always used to have band meetings in our local pub – the Three Tuns in Beckenham. We were well aware of the David Bowie connection (in his early incarnation as a folk singer he appeared here most Sunday nights), and knew The Man Himself had a house nearby.

He didn’t influence us musically but had our total respect. He was the Local Boy Made Good. It gave us hope.

Tennis Shoes made a single but that was that. No rock stardom for me. And then I became a music journalist.

In the early Eighties Bowie was the ultimate deity. The New Romantics wouldn’t have existed without him. Neither would Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, Culture Club, any number of bands from that era.

I remember interviewing Steve Strange around the time he appeared in the Ashes to Ashes video. If anything he was more excited about that than his band, Visage.

Every move Bowie made was observed and analysed, often badly copied but never surpassed.

My only encounter with him was in 1991 when I worked for the NME. My then partner, Kevin Cummins, had been invited to photograph Bowie in Dublin so I tagged along.

I remember arriving at the recording studio where we were to meet, going to the café and finding it deserted.

We sat down at a table and waited. A few random people arrived but no sign of The Great Man.

I hadn’t even noticed there was a leather jacket on the back of my chair. Then someone came up behind me and politely said “Excuse me,” pulling it away. I swivelled round and came face to face with Him.

How bloody embarrassing. I was sitting in David Bowie’s seat.

Things descended into farce when we were invited into the studio itself to listen to Tin Drum play a few tracks from their new album to a small audience of press people.

When no one applauded at the end of the first song, there was an awkward silence. When no one clapped at the end of the second song, Bowie reprimanded us.

How bloody embarrassing. A private David Bowie gig for a bunch of hacks who were trying to be cool and cynical.

Only it wasn’t really a David Bowie gig.

It was bloody Tin Drum. And no one liked Tin Drum, did they?

After that, I didn’t feel I could speak to him. From a respectful distance, I watched as Kevin took his photographs. Bowie was courteous, the complete professional.

Even though we were physically close, there was an invisible wall between us. It took me back to my teenage years, when I was outside looking in to a club I could never join.

They say you should never meet your heroes. Bowie wasn’t really my hero, though. He didn’t belong to me. He belonged to the cool kids.

But I was still star-struck, even though I’d been a music journalist for almost 15 years. And I can’t think of many artists who would have had that effect on me when I was a jaded rock hack.

I’ve immersed myself in the personal tributes to Bowie. It’s hard to top Suzanne Moore’s in The Guardian. But another journalist friend of mine, Clair Woodward, has written a brilliant one. As she said, you just have to write something. He was that much a part of our lives.

Perhaps this is the definitive funeral of our youth. Gone, never forgotten.

Postscript: After a week of gorging myself on insightful reminiscences and personal tributes from Bowie collaborators, commentators and fans, I had a dream.

We had an intensely close relationship but it was a secret. He was elusive. I walked into a room hoping to see him – surely it was him – but no, it was a lookalike.

Then the picture started to pixillate. ‘Reality’ broke apart. And I was told that it hadn’t happened. It was a dream within a dream. The relationship didn’t exist. Never had done. I was inconsolable. Deeply distraught and alone. I woke up crying over something I never had that wasn’t real. But the tears were.

Leave a Reply