Here is the second extract from my memoir Hit Girl: My Bizarre Double Life in the Pop World of the Eighties. It is September 1980 and, under my pen name Betty Page, I have just been appointed a staff writer at the music paper Sounds after spending a year being the editor’s secretary by day and secret music journalist by night. My first assignment is a tough one: to secure the first music press interview with elusive darlings of the London club scene, Spandau Ballet. This is the story of what happened…

The Blitz Kids arrived at the perfect moment, just as I was developing the confidence to step boldly into a different kind of wardrobe. I loved their flamboyance – the frocks, the furs, the frills, the flirting and the frisson of unusual sexuality.

The Kids were stars in their own theatre and I wanted a bit part in the production. But I wasn’t up for audition – for two good reasons. First, like the members of any close-knit community, they didn’t welcome outsiders. Second, I wrote for a music paper. They hated rock music and all who thrived on it. They wished to spit on its grave.

Whatever their personal style, they were united in their love of dance music and the clubs that played it. Most of them – and particularly the Blitz house band Spandau Ballet – ignored the music papers.

As the autumn of 1980 approached, Spandau had become one of the most talked-about groups in London. They didn’t play “gigs” as such – they held “events”, playing in unusual venues such as the HMS Belfast, a ship permanently docked on the Thames, to invited audiences only. They rapidly became the focal point around which the Blitz scene revolved. Their fans, most of whom were also friends, were as important as the band and their music.

In their short career, Spandau Ballet had already been the subjects of a television documentary and were about to release their first single on a major record label. They weren’t the least bit interested in being interviewed by the music papers, which they quite rightly associated with unkempt rock herberts in flared denim. More shockingly, they didn’t need the press.

But Alan, the editor, was determined to get them into Sounds and I was desperate for my first major assignment as a staff writer. He knew that I wasn’t a natural defender of the rock ’n’ roll tradition and might be the secret weapon he needed to penetrate what was dubbed The Cult With No Name.

Most dyed-in-the-jeans music hacks hated the idea of being bypassed by a bunch of sharp-suited upstarts, so Spandau had been dismissed by them as elitists, fops, dandies, upper-class twits and even fascists, because of the Nazi connotations of their name.

It didn’t help that the Ballet boys deemed fashion to be of equal importance to music. The fact that they were actually working-class Labour supporters from north London didn’t seem to count.

And so it was with a combination of naïve enthusiasm and blind panic that I called Spandau Ballet’s manager, Steve Dagger. I had no reason to believe he’d give me the time of day – the last thing he needed was another stitch-up job by an ignorant music hack. But Steve quickly realised that I was something of a blank canvas upon which he and Gary Kemp, their chief theorist and songwriter, could paint their ideas. But he wasn’t going to give me the interview easily.

I managed to persuade Steve that I had no hidden agenda and that my interest was genuine. He told me I would have to do some research before I met the boys, so I was summoned to watch the documentary that Janet Street-Porter had made about the band and their fans for the 20th Century Box series. I knew he was making me jump through hoops but I had nothing to lose.

When I’d done everything the manager had asked me to do, he grudgingly gave me permission to speak to Gary – as long as he was there too. Steve was the sixth member of the band, the master strategist; Gary was an intense, idealistic young man responsible for Spandau Ballet’s image and agenda.

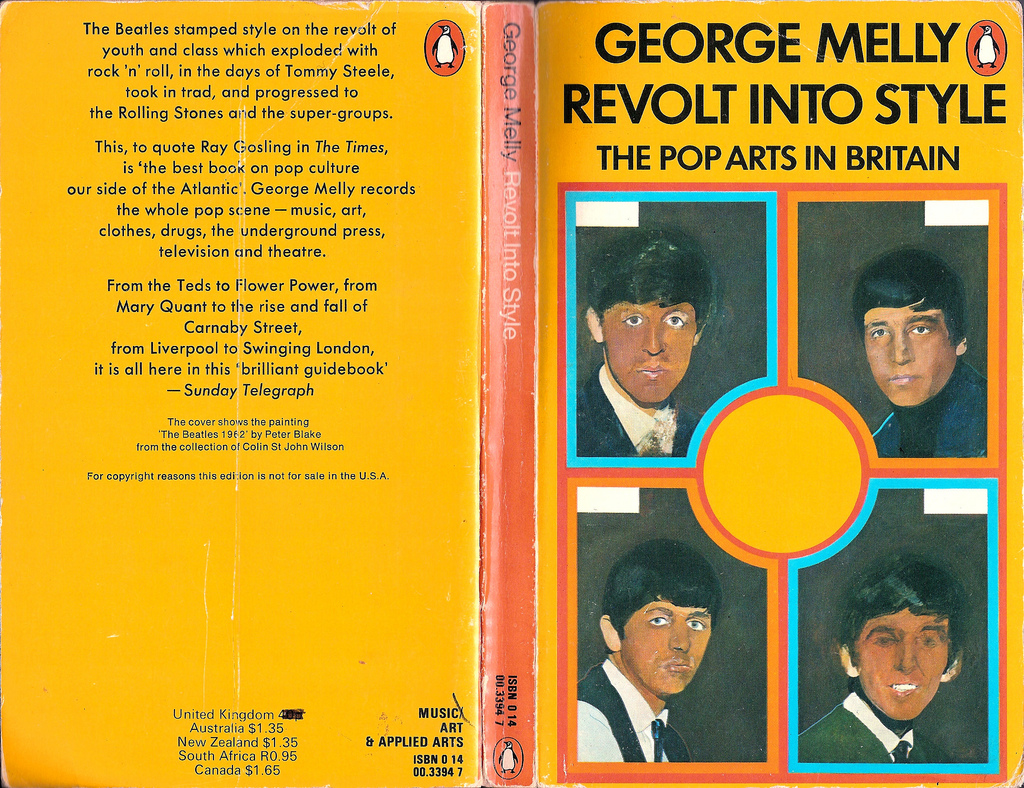

As I sat down to interview the pair, Gary fished out a well-thumbed copy of George Melly’s book Revolt Into Style and read out a passage about the true meaning of Mod being a small group of young working-class boys forming a mutual admiration society “totally devoted to clothes”.

I carefully copied down the words without taking them in. I had to check again – was he telling me that when the band first met, it was only about dressing up? “Yes, basically it revolved around admiration of clothes,” interjected Steve before Gary could open his mouth, “and featured extreme posing.” Extreme posing: words to strike fear into the heart of any rock music purist.

Since punk, Steve told me, it had been a case of the most stylish people wanting nothing to do with rock music or the media. “These people wanted to go to soul clubs, to dance, to dress up,” he said. “The innovators are really pushing the fashion thing a bit further, making their own clothes, maybe buying some chain-store stuff, but using it differently. Why the music papers haven’t picked up on it I don’t know.”

Gary did. “The thought of people like us spending money on looking good – they just can’t stand it,” he fumed. “I don’t think they like the idea of fashion as a progressive force. But it’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

I wanted to tell him “progressive” was an adjective that only applied to “rock” in my world. But I let that one go.

“The scene attracts people who want to develop, who want to achieve something, whether it’s for art or money,” said Gary.

“It all started with our first gig,” continued Steve. “We invited about 10 young fashion designers, 10 hairdressers, and a couple of people who run clubs. We thought they’d like us and they did. It’s much easier when you’re surrounded by people like that – not only hairdressers and clothes designers, but also graphic designers, photographers, even people who write for us.”

It was this image of the self-contained creative elite that so horrified the music papers – along with the constant reference to hairdressers, of course.

Steve was very keen for me to understand that Spandau Ballet were not a bunch of art students. Gary and his brother Martin had grown up in Islington with little money but a lot of attitude, mixing with the sort of blokes who’d blow their entire wage packet on a flash pair of trousers or shoes.

“If you haven’t got anything, then you should make the most of your appearance,” said Gary. “If that’s all you’ve got, beat everyone at it. As far as a poseur is concerned, he is his own work of art. The human sculpture.”

I suddenly felt hyper-conscious of the charity-shop suit I was wearing. Boy George certainly qualified to be installed in a gallery; I did not. And I wasn’t expecting to figure on the Blitz Kids’ best-dressed list any time soon.

But Betty Page, novice staff writer, had done a good job. My hard-earned interview with Steve and Gary appeared on the cover and centre spread of Sounds in September 1980 under the headline “The New Romantics – a manifesto for the Eighties”. Hey presto, a youth movement was born.

© Beverley Glick 2005. All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply